Tendonous Windgall Worries

‘Windgall’ is a term commonly used by vets and owners to describe fluid swellings behind the fetlock in horses and ponies. While in many cases they are considered non-painful blemishes, it is important to understand why they occur and when they should be investigated, as they could affect your horse’s future soundness.

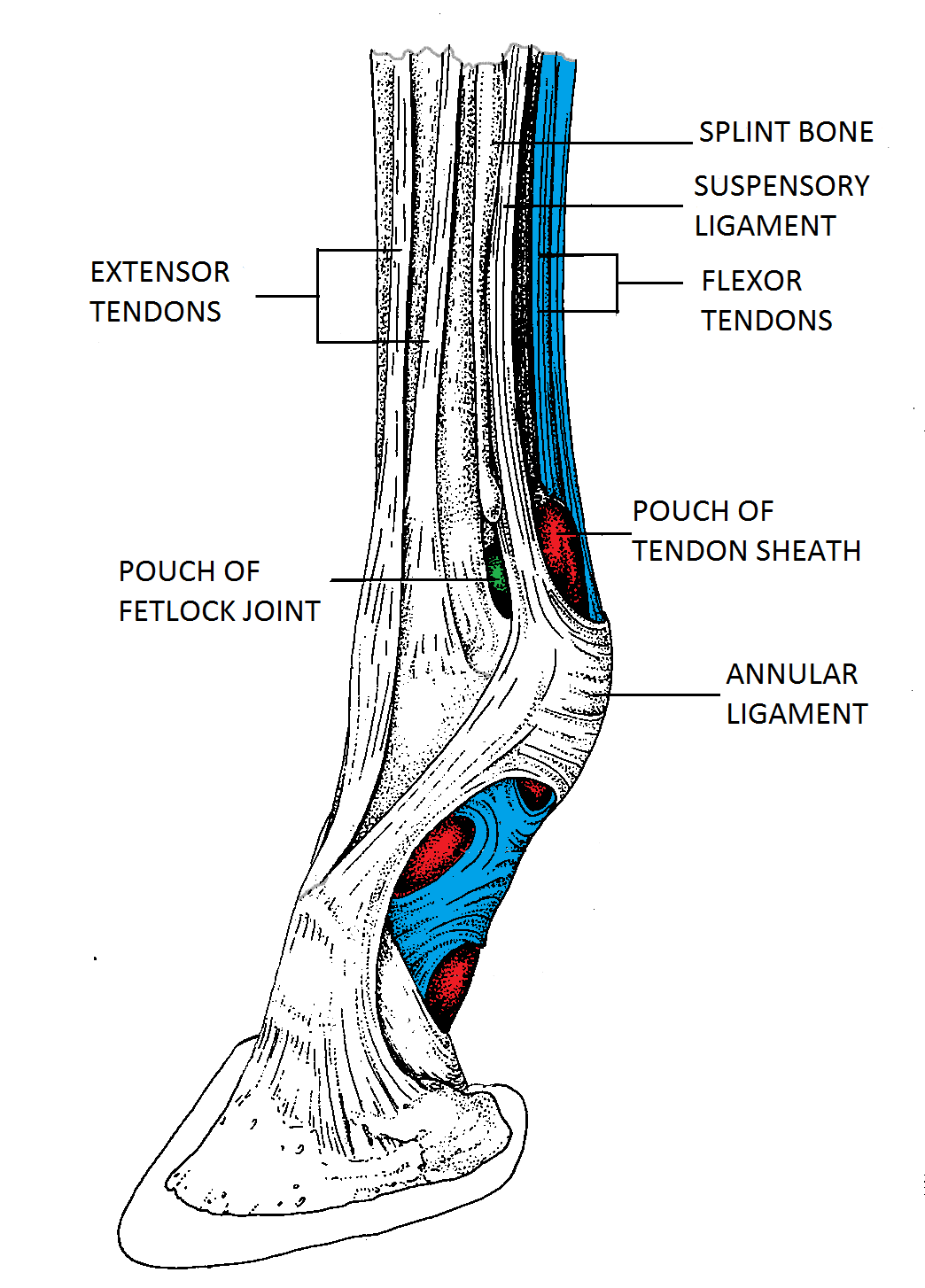

Windgalls can be seen in any breed, but are more common in cob types, hunters and older horses. They can affect forelimbs but are more common in the hindlimbs and can occur on either one or both limbs. Appreciating the normal anatomy of the leg helps understand how windgalls form (Fig 1)

Windgalls occur in two types; ‘articular’ (joint) and ‘non-articular’ (or tendinous) windgalls. Articular windgalls occur when the small pouches at the back of the fetlock joint become distended, these fluid swellings are part of the fetlock joint per sec. For the rest of this article articular windgalls are not discussed further.

Tendonous windgalls occur within the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS), the structure which runs down the back of the limb forming a tunnel for the two flexor tendons (Fig 1 and 2). Relative narrowing of this tunnel displaces fluid into the pouches that form tendinous windgalls. Any tendon sheath is lined by a synovial membrane which produces fluid which helps to reduce friction between the tendonous tissues during movement and provides nutrition to the living structures. When these structures within the tendon sheath are injured or inflamed an excess of fluid will be produced as the horse’s body tries to repair and it’s the resultant swelling that is then called a windgall.

It is now recognised that most tendinous windgalls arise due to damage to one or either of the two tendons within the DFTS. The damage is usually in characteristically typical sites, these include: a longitudinal tear to the outside of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT); a central ‘core’ lesion within the DDFT; damage or rupture of the manica flexoria (MF) of the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT); or damage to the distal manica in the pastern. (The two manica structures(flexoria or distal) are “washer” type structures that originate from the SDFT and wrap around the DDFT and are thought to stabilise the two tendons in their normal position). In some occasions a tendonous windgall may arise due to damage to the annular ligament that helps create the fetlock canal through which the DDFT and SDFT run. In years gone by damage to the annular ligament was thought to be the main reason for the formation of tendinous windgalls but it is now appreciated that the incidence of primary problems to this structure is much lower than previously thought.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

Many apparently normal horses may have small, soft and symmetrical windgalls with no signs of lameness. These can be caused by low grade wear and tear, particularly in horses working and jumping on poor going or hard surfaces. They may reduce in size following exercise and these windgalls are of little significance.

Some tendinous windgalls can however be significant and associated with lameness or poor performance, so it is important to recognise them and act accordingly. Affected horses may present with a gradual or sudden increase in the size of the swelling. There is usually also heat, pain and/or lameness associated with these horses. Initial treatment should include box rest, cold therapy (e.g. ice packs/wraps) and supportive stable bandages while advice is sought. Your vet can give you further guidance on whether the horse needs seen as a matter of urgency or make arrangements for further investigation.

INVESTIGATION

The vet will thoroughly examine the horse’s limbs and assess for lameness. Nerve blocks with local anaesthetic can then be used to determine if the lameness is related to the windgalls.

With windgalls both x-ray and ultrasound prove useful. Good quality x-rays can detect any bony changes around the fetlock region, while ultrasound can look in detail at the tendons and ligaments associated with the sheath. The vet can see thickening of the synovial membrane, holes or tears within tendons and ligaments, thickening of the annular ligament and adhesions between the tendons and digital sheath. Although ultrasound is very helpful it may not pick up all lesions and, in these cases, other imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan) or tenoscopy (key-hole surgery) can be used.

TREATMENT

Many horses with windgalls that are not causing lameness can be easily managed allowing the horses to live actively and not inhibit the horses’ ability.

However, windgalls that cause lameness usually require a period of rest to recover followed by a gradual reintroduction to controlled exercise. How long will depend on the type of injury. Bandages are often useful initially in reducing swelling but must be applied correctly with plenty of padding. Any pre-existing issues with shoeing and foot balance should be addressed with cooperation between qualified farrier and veterinary surgeon. In addition, anti-inflammatory medication is often indicated, either systemic such as phenylbutazone (bute) in feed, or direct injection into the affected tendon sheath. This intrasynovial medication must be performed under sterile conditions and allows the vet to instil beneficial drugs such as corticosteroids and/or joint health promoters (e.g. hyaluronic acid).

Unfortunately, some cases of tendonous windgalls do not respond to the above treatment, usually as a result of the extend of the tendon or ligament damage associated with the sheath. In these cases tenoscopy of the sheath is indicated (keyhole surgery). This is particularly the case with damage to the manica flexoria and longitudinal tears to the DDFT. The advantages of this procedure is that the injury can be observed directly so the full extent can be seen and treatment can be performed at the same time (Fig 3). This may involve removal and tidying up a frayed torn tendon or ligaments and flushing the interior of the sheath with sterile fluids to remove inflammatory debris. Transection (cutting) of the annular ligament can also be undertaken by a very small incision with minimal aftercare. After having assessed all the sheath the surgeon will be able to give the horse owner a very accurate prognosis for the horses future soundness.

For some cases specialised treatment such as the use of stem cells, PRP or IRAP is indicated. Alternative therapies can have a role to play, but should not be a substitute for professional veterinary treatment.

SUMMARY

The prognosis for a horse with windgalls with an associated lameness depends on the precise cause, prompt treatment and good management during recovery. Horses that have small symmetrical windgalls with no lameness or performance problems can often lead normal competitive careers as long as well managed. Remember, any new swellings should be checked out promptly by a vet and then regularly monitored by you for any changes.

Fig 1 – normal anatomy of the tendons and digital flexor tendon sheath in the lower limb.

Fig 2 – large tendonous windgalls that appeared suddenly. The swelling was painful to touch and the horse was lame at trot. These should always be investigated.